Thando Vilakazi

Representatives of competition authorities from various African countries frankly discussed cartel penalties, settlement and leniency programmes at the CCRED Annual Competition and Economic Regulation Week in March 2015 in Zimbabwe.1 In this discussion, authorities highlighted the challenges of enforcement actions involving complex collusive conduct, the need for deterrent penalties, the lack of local case precedent developed through rigorous contested hearings, and the resource constraints which hamper enforcement actions and deterrence in particular. In this article, we consider the current state of affairs in terms of penalties, settlements and leniency programmes across jurisdictions in the region.

Why does busting cartels matter?

Uncovering cartels, prosecuting offenders and enhancing deterrence is especially topical across various jurisdictions in Africa. Now, more than ever, competition authorities are pursuing ways to enhance their ability to detect and penalise cartel conduct. This trend is linked to the growing body of evidence that cartel conduct is widespread across African countries2, the fact that competition law enforcement is now well-established in various countries3, and the fact that some newer authorities are reaching ‘maturity’ in terms of the resources and institutional capacity that they have to pursue investigations of complex conduct rather than simply, and justifiably focusing on merger control in the early years.

Cartels, as prohibited arrangements between firms in a horizontal relationship to fix prices or quantities in the market, are notoriously difficult to uncover partly because firms have strong incentives to hide the fact that they are jointly benefiting from extracting supra-competitive rents through illegal conduct at the expense of consumers. Cartelists come together to jointly maximise profits in a market through agreeing on key competitive parameters such as price in order to prevent costly price wars that can reduce the profits of all insiders to the arrangement. Cartelists restrict or deal aggressively with entrants that look to come into the market to ‘disturb the peace’ by undercutting cartel prices. Market outcomes resulting from cartels are therefore akin to monopoly outcomes in the market, which in most cases mean higher prices and reduced demand overall for affected goods and services in an economy. Whereas firms are expected to execute independent, best response strategies in a competitive market related to their individual costs and market conditions, colluding firms agree on mechanisms to monitor one another and punish firms that fall out of line with jointly agreed strategies.

International studies have shown that cartel conduct, including where there are high levels of information exchange, is harmful and cartel mark-ups are generally in the region of 15-25% of the cartel price.4 Most recently, the EU Court of Justice in its landmark banana importer cartel decision involving Dole Food ruled that communication between competitors which results in price-fixing is per se anticompetitive and does not require an analysis of the effects of the conduct on competition in the market.5 Several South African studies have also found high cartel overcharges, as a measure of how much cartel prices exceed the prices that would prevail under competitive conditions in a market, comparable to and in some cases higher than those found in international studies.6

Dealing with cartels: penalties, settlements and leniency

It is therefore interesting to consider the strategies that authorities employ to uncover and punish offenders. Cartel deterrence is about altering the incentives of firms in deciding whether to engage in or continue with collusive conduct. Firms consider the benefits (profitability) of the conduct and weigh these against the likelihood of getting caught and the penalty they expect to receive if they are caught. 7 A credible threat is created by the competition regime when the likely penalties are high. 8 This is especially true for developing jurisdictions where the probability of getting caught is especially low due in part to resource constraints which also affect the ability to conduct ex-ante scoping exercises to find cartels.

Penalties, settlements and leniency work together to create deterrence. Penalties, which are provided for in competition legislation, directly penalise conduct whereas corporate leniency programmes (CLPs) are designed to encourage firms to come forwards and confess collusive conduct in exchange for a substantially reduced penalty – in most cases, a zero penalty for the first firm to come forwards. The latter would typically be on condition that firms provide evidence about the conduct which assists the authority to prosecute remaining cartelists. Settlement lies somewhere in between in the sense that firms may admit to collusion, particularly where they may not have been the first to come forwards and leniency has already been granted to another firm, and reach an agreement with the authority for a reduced penalty in exchange for substantial cooperation in terms of evidence provided.

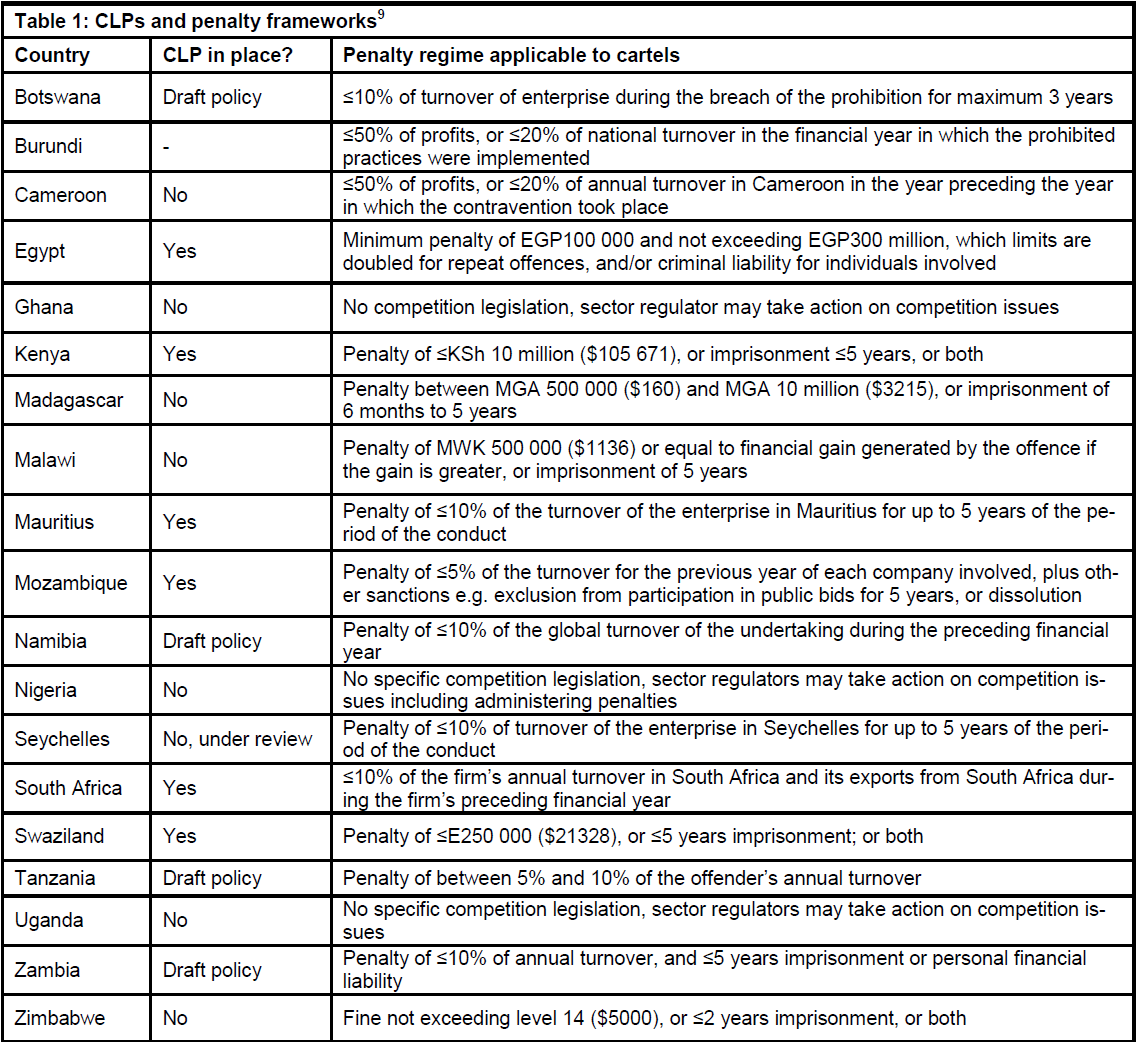

In this context, settlements and leniency can be viewed as providing incentives for firms to come forwards while penalties, if sufficiently high, play a punitive role. Across several jurisdictions there are significant differences in the penalty frameworks, and leniency programmes are not widely applied as yet (Table 1).

The range across countries in terms of the penalty regime applied is wide, with some jurisdictions such as Namibia that have scope in the legislation to apply penalties up to a cap of 10% of the global turnover (although penalties applied need not be of global turnover) of the enterprise (similar to the European Commission’s provisions) and others such as Zimbabwe and Madagascar with very low caps on financial penalties. In some cases, low fines may be accompanied by some form of personal criminal liability including up to five years imprisonment.

The financial amounts that are paid by offending firms are also affected by the extent to which the duration of the conduct is considered. For instance, in Botswana and Mauritius there is a clear limitation on the number of years of the conduct for which a penalty can be applied. While this type of clause may serve to protect firms from extremely large fines that can lead to financial difficulties, it also prevents firms from being penalised fully in cases where the cartel arrangement may have lasted for a very long period of time. Where there is a further cap on the total fine amount relative to turnover which can be levied, firms that have been involved in egregious conduct for a long period, are effectively given an even larger discount on the fine they would have received absent the limit on duration and turnover, which reduces the likely deterrence of future conduct. In South Africa, the authorities have only recently moved to considering more explicitly the duration of conduct in the determination of penalties and settlement through recent decisions of the Tribunal and the draft settlement guidelines of the Competition Commission. 10

It is clear that a cap on penalties which is too low, especially when applied to a single-product firm or a narrow affected turnover, will not deter. Importantly, this also affects the likely success of a leniency programme or settlements procedure. This is because firms will face less incentive to come forwards and confess to conduct if they could, after paying a small penalty, get away with not admitting to the alleged conduct at all. In exchange for paying a low fine, the firm essentially also gets away with not having to provide the competition authority with any additional information about the cartel. The corollary is that the authority does not benefit from the resource-savings of settling or entering an arrangement with a leniency applicant, nor the savings from not engaging in costly investigation and litigation procedures.

Challenges in developing jurisprudence

The use of settlement and leniency programmes, as well as the interpretation of the penalty framework may come with some difficulties in the initial stages of implementation. For instance, in the absence of case law which tests the various provisions, there can be some doubt regarding the interpretation of the requirement in Botswana’s law to show that the firm must have ‘negligently’ and ‘intentionally’ engaged in the conduct before a penalty can be levied. In Zambia, the size of the penalty is determined using a formula and fines of over US$20 million determined by the authority against firms in the fertilizer industry in 2013 were appealed by the firms involved, and the matter is still to be heard in higher courts.

In South Africa, the introduction of the CLP in 2004 contributed significantly to the number of cartel cases uncovered since, although it took around three years before firms started coming forwards under this programme.11 Importantly, in the early years, the authority also applied its discretion in interpreting this policy and in one case awarded leniency to more than one firm where the second firm to come forwards had provided information and evidence relating to further conduct beyond what the leniency applicant had provided.12

There are some important lessons here. It is important for authorities to grab the low-hanging fruit in terms of prosecuting cartel conduct. This relates to those cases which can be initiated and finalised on the basis of information from a leniency applicant and/or firms that subsequently come forwards to settle. Successfully prosecuting firms in these cases and publicising this widely, contributes to creating deterrence of future conduct in the economy. However, this relies on the principle that any agreement entered into with a leniency applicant or a settling firm is based on a clear, strong requirement that the firm cooperates meaningfully with the authority. This entails providing evidentiary support which is reliable and accurate to assist in the prosecution of remaining firms. Importantly, while it could be argued by the public that leniency and penalty discounts allow firms to ‘get away’ with having committed offences under the competition legislation, it is clear that preventing anticompetitive conduct from continuing to harm consumers well into the future is even more important. Given the contestability of fines in court, as in the case of Zambia, and the wide acknowledgment that penalties generally do not and cannot (given statutory caps) equate to the total damage caused by cartel conduct13, preventing the conduct from causing continued damage become even more critical. The evidence on cartel mark-ups certainly shows that the harm is significant, and absent a strong culture of follow-on damages claims in countries in the region penalties are unlikely to account for all of the harm caused, including the losses in terms of innovation, quality and variety in the market over time which are extremely difficult to quantify.

On this last point, it is to be expected that authorities do not apply fines that directly match the size of the harm caused (statutory caps aside) because this harm is difficult and resource-intensive to quantify which is perhaps why harm is presumed in many jurisdictions. Furthermore, in the case of settlements, and where the conduct has gone on for so long that it is difficult to define a competitive counterfactual period, it is simply not feasible to go through the exercise of determining the exact extent of harm. This is not a useful application of the authority’s resources and time, which is why authorities can benefit from retaining their discretionary powers in the case of settlements.

For authorities with relatively new leniency programmes including those that are under review or in the drafting stages, such as in Tanzania, Botswana, Zambia, Swaziland and Namibia, a similar level of discretion is important to allow the authority to consider the merits of each case and each applicant on a case-by-case basis, whilst providing the desired certainty for firms. One example where this matters is in distinguishing between firms on the basis of the extent of cooperation with the authority which may take on a different form across cases, or differ according to whether the firm was the second or the last to come forwards to settle the matter.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the approach of authorities in terms of penalties, settlement and leniency is best improved through learning-by-doing and in contested cases. However, as was abundantly clear in the discussions between authorities, there is even more to be learnt from the experiences of neighbouring authorities and sharing between authorities. The record is poor in this regard. This may be due, in part, to the differences in the legislation in each country. However, where the common goal is to enhance deterrence through uncovering and penalising cartel conduct, there should be sharing between countries in terms of mechanism for avoiding the challenges that come with successfully penalising firms, and effectively implementing leniency and settlement programmes

A PDF copy of the article is available here.

Notes

- The inaugural CCRED Annual Competition and Regulation (ACER) Week was held at Victoria Falls from 16 to 21 March 2015, hosted through a partnership between the Zimbabwean Competition and Tariff Commission and CCRED. Information on the various short learning training programmes and the conference proceedings are available on the CCRED website.

- See Roberts, S., Simbanegavi, W., and Vilakazi, T. ‘Understanding competition and regional integration as part of an inclusive growth agenda for Africa: key issues, insights and a research agenda’, Paper presented at the Competition Commission and Tribunal Annual Conference, Johannesburg, 2014; and Kaira, T. ‘A cartel in South Africa is a cartel in a neighbouring country: Why has the successful cartel leniency policy in South Africa not resulted into automatic cartel confessions in economically interdependent neighbouring countries?’ Paper presented at the Annual Competition and Economic Regulation Week Southern Africa, 16-21 March 2015, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe.

- Zengeni, T. ‘Update on the COMESA Competition Commission’ (April 2014). CCRED Quarterly Competition Review.

- See, for example, Khumalo, J., Mashiane, J. and Roberts, S. (2014) ‘Harm and Overcharge in the South African Precast Concrete Products Cartel’, Journal of Competition Law and Economics; Motta, M. ‘On cartel deterrence and fines in the European Union’, European Competition Law Review, (2008) 29(4) 209; Werden, G. J. ‘Sanctioning cartel activity: Let the punishment fit the crime’, European Competition Journal, (2009), Vol. 5(1), p. 19-36; and Wils, W. ‘Optimal antitrust fines: theory and practice’, World Competition, (2006), Vol. 29(2).

- European Union Court of Justice. Judgment of the Court (19 March 2015), Case No. C-286/13 P.

- See Khumalo et al (2014); Mncube, L. ‘The South African Wheat Flour Cartel: Overcharges at the Mill’, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, (2013), 13(4); Boshoff, W. ‘Illegal overcharges in markets with a legal cartel history: the South African bitumen market’, CCRED Working Paper No. 3/2013; and Das Nair, R., Mondliwa, P. and Sylvester, A. (2014), ‘Assessment of the long steel cartel: rebar overcharge estimates’, Presented at Competition Commission and Tribunal Annual Conference, GIBS, Johannesburg, 4 and 5 September 2014.

- See Wils (2006); and Edwards, K. and Padilla, A. J. ‘Antitrust settlements in the EU: Private incentives and enforcement policy’ in Claus-Dieter Ehlermann and Mel Marquis (eds), European Competition Law Annual 2008: Antitrust Settlements under EC Competition Law (2008).

- See note 4.

- Table has been drawn largely from Bowman Gilfillan Competition Law Africa publication and the webpages of the different competition authorities.

- See Competition Tribunal of South Africa, Competition Commission v Aveng & others, Case No. 84/CR/Dec09; and Competition Commission of South Africa, Guidelines for the determination of administrative penalties for prohibited practices (1 May 2015), available online.

- Muzata, T. G., Roberts, S. and Vilakazi, T. ‘An economic review of penalties and settlements for cartels in South Africa’. CCRED Working Paper No. 9/2012.

- See note 11.

- See Aguzzoni, L., Langus, G. and Motta, M. ‘The effect of EU antitrust investigations and fines on a firm’s valuation’, Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 61, Issue 2, June 2013, p. 290-338; and Combe, E. and Monnier, C. (2009). ‘Fines against hard core cartels in Europe: The myth of over enforcement’, Cahiers de Recherche PRISM-Sorbonne Working Paper.