Big Pharma leveraging their dominance on consumers

Shingie Chisoro-Dube

In the developing world, disease and poverty are interdependent making access to essential medicines at affordable prices even more critical. 80% of the two billion people worldwide without access to essential medicines live in low income countries. As such, competitive rivalry in the pharmaceutical industry can improve access to medicines by reducing prices and through motivating brand companies to challenge existing patent drugs and create new and improved medicines. Furthermore, upon expiration of patent drugs, competition encourages generic companies to provide less expensive alternatives of medicines.

In June 2017, the Competition Commission of South Africa launched an investigation against three major pharmaceutical manufacturing companies for alleged excessive pricing of cancer drugs – Roche, Pfizer and Aspen Pharmacare. Roche, a Swiss company and Pfizer, an American company, are two of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Aspen Pharmacare, a South African company, although not in the global top twenty pharmaceutical companies, is the sole manufacturer and supplier of off-patent cancer drugs for blood‚ bone marrow and ovarian cancers. Aspen acquired the license and marketing rights from the originator GlaxoSmithKline after the patents expired in 2009.

All three companies have sole rights to distribute different cancer drugs in South Africa. Roche and Pfizer are sole suppliers of the breast and lung cancer medicines, respectively, while Aspen Pharmacare is the only supplier of three generic cancer medicines. The investigation follows a number of similar investigations against the same companies by other competition authorities internationally, including the European Commission (EC), the Italian Competition Authority and the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).

The Competition Commission of South Africa dropped charges against Aspen Pharmacare in October 2017 citing that an excessive pricing case could not be sustained against the company. The Commission noted that the revenues generated by the drugs in question (Myleran, Alkeran and Leukeran) were very low due to few patients using the drug. Furthermore, the drugs presented limited prospects in the market as they were approaching their lifespan. Nonetheless, the fact that Aspen is the sole manufacturer of the medicines raises competition concerns.

International competition cases against pharmaceutical companies

In May 2017, the EC launched an investigation against Aspen Pharmacare for alleged excessive pricing of five off-patent cancer drugs for blood‚ bone marrow and ovarian cancers. Aspen Pharmacare is alleged to have imposed price increases up to 4000% in a number of European countries at specific points in time between 2012 and 2016. The price increases were not gradual annual increases over a four year period but significant price increases made at specific points observed during the period under review. For example, in England and Wales, Aspen Pharmacare increased the price of Busulfan used by leukaemia patients by 1100% from £5.20 to £65.22 a pack during 2013 while the price of Chlorambucil also used to treat blood cancer increased by 385% from £8.36 to £40.51 a pack during the same year. In Spain, Aspen Pharmacare is being investigated for increasing the price of a cancer drug by 4000% and causing a deliberate drug shortage in order to charge excessive prices between 2012 and 2016.

In September 2016, the Italian Competition Authority imposed a fine of €5 million on Aspen Pharmacare for increasing prices of cancer drugs by 300% to 1500% higher than the original price since the approval of the drug in Italy in 2013. Prior to this conduct, Aspen Pharmacare had threatened to withdraw the drugs from the Italian market.

Similarly, in December 2016 the UK’s CMA imposed a record fine of £84.2 million on pharmaceutical manufacturer, Pfizer, and a fine of £5.2 million on distributor Flynn Pharma, for charging excessive prices for a generic anti-epilepsy drug, Phenytoin Sodium. These companies increased prices by up to 2600% between 2012 and 2013 after de-branding of the drug to become a generic drug. The CMA cited that it could not find any justification for the significant price increases as these were old drugs without recent innovation or investment costs to be recouped.

The above excessive pricing cases involving Pfizer in the UK; and Aspen Pharmacare in the EU and Italy; all relate to generic drugs. Generic drugs are expected to be generally cheaper than patent or branded drugs because generic drugs can be manufactured by any company not just the developer of the original drug. Price competition between multiple manufacturers is expected to lower prices of generic drugs and therefore they are not subject to price regulation. On the other hand, pricing of original or patent medicines is heavily regulated and generally expensive as a way to provide incentives for future innovation. Pricing of new drugs is designed in such a way as to cover past and future R&D expenditures.

Lack of price regulation and limited entry in generic drugs can lead to excessive pricing of generic drugs especially in cases where a single company has sole rights to manufacture and distribute the generic drug within a particular geographic market. This raises the issue of parallel imports as a way to promote price competition between local manufacturers and imports. Parallel imports refer to importation of legitimately produced drugs for resale into a country, without the authorisation of the patent holder or owner of intellectual property rights of the specific drug. Parallel imports of pharmaceutical drugs involve taking advantage of a price difference between two countries. Increased competition with parallel imports results in lower prices of the drug, other things equal. However, the price benefits of parallel imports are inconclusive in countries in the European Union where parallel imports are permitted.

It goes without saying that competition requires the presence of effective rivals and market conditions free from agreements which may limit the ability of competitors to contest the market. The nature of arrangements in the pharmaceutical industry as described above suggests a need for more stringent competition rules, although this needs to be balanced with the characteristics of the industry including patents and intellectual property rights which make it prone to competition prosecutions. Importantly, the incentive of companies to invest in R&D and earn profits from protection of rights to intellectual property is a critical dimension of competition in the industry, although these rights can also be abused.

The global pharmaceutical industry

Given the widespread and global nature of the above cases, it is important to reflect on global trends to determine the extent of market power exerted by the individual firms.

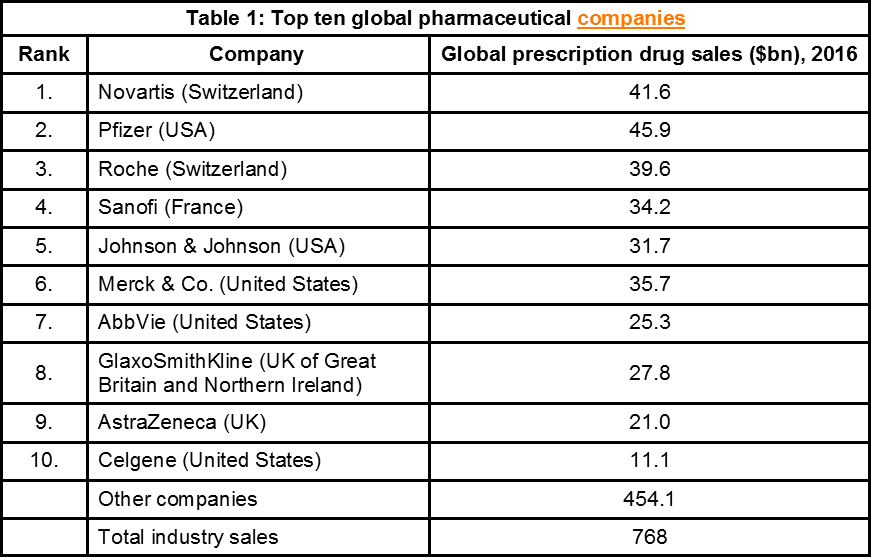

The four largest pharmaceutical companies account for 21% of global prescription drug sales in 2016 (Table 1). As the concentration ratio measure of the largest four companies (CR4) is less than 40 percent, the pharmaceutical industry is generally not regarded as a concentrated industry on this basis. However, while the individual companies may not be dominant in terms of the firm shares of global sales, the exclusive rights that come with supplying specific drugs create dominant positions in particular drug (product) markets.

To determine the extent of market power in the cancer drugs market as per the above cases, Table 2 shows global sales of cancer drugs in 2016, noting that there may be further sub-markets relating to the treatment of specific types of cancer which could be even more concentrated. The largest four companies account for 50% (CR4) of global cancer drug sales, which clearly shows concentration at a product level.

Despite concentration in individual product markets which raises competition concerns, the global firms have an important role to play in the industry in terms of investments in research and development (R&D). The pharmaceutical industry as a high-technology and knowledge-intensive industry is driven by large investments in R&D. On average, R&D costs equate to 19% of global prescription drug sales. Given the costly and cumbersome administrative regulatory processes associated with the development of a drug, only the largest firms are financially equipped to conduct the majority of the R&D investments in the industry and also hold the majority of patents as the originators.

The implication is that barriers to entry are high. These patents have a lifetime of 20 years from filing with an extension of five years in most OECD countries. The smaller pharmaceutical companies mainly manufacture off-patent products or manufacture drugs under license to a patent-holder. This raises a key issue regarding the appropriate duration of patents as they are required to allow sufficient time for recoupment of the costs of R&D investments and for companies to earn profit from their investments as noted above. The challenges associated with quantifying the actual costs of R&D across different drugs makes it difficult to determine the appropriate duration of patents. Furthermore, although a pharmaceutical company may file for a patent application soon after a drug discovery, clinical trials necessary for drug approval may take several years before the drug is commercialised, the effect being to shorten the effective life of the patents.

Although patents stimulate innovation and reward firms for R&D investments, global pharmaceutical companies may use patents to reinforce market power in specific product markets. The monopoly and exclusive rights provided by patents prohibit rival manufacturers from producing or selling the same product resulting in high prices and limited access to medicines. Although generic drugs are regarded as the most effective and sustainable way to reduce the price of drugs due to competition, the above cases show that lack of competition even in markets for off-patent drugs leads to high prices. Furthermore, in the context of the South African investigation, it is likely that concentration in specific product markets or to supply the domestic market may mean high prices relative to competitive benchmarks.

Abuse of patent rights to charge unjustifiably high prices raises issues about the need for compulsory licensing whereby companies can apply for the license to produce a patented medicine without the consent of the patent owner. This can be done be done through arrangements that ensure licensing on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. However, this approach needs to take into consideration the incentives of firms to engage in R&D and future innovations noting that under license patents holders may also benefit financially from licensing their technology to other companies. While it is important to reward firms for R&D investments, the rights they enjoy should not be used to reinforce dominant positions in the market, increase prices unjustifiably, and limit entry of new players particularly as greater competition can lead to further innovation as companies fight to gain and maintain market share.